One of the stranger aspects of being a modern author is the expectation that those who have sweated blood over a keyboard must then sign by hand thousands of printed copies, as if the thing had been painstakingly produced by some medieval monk.

But all the talks and signings do have the merit of taking you to new places. Bath, for example, is not a city I know well. Nothing connects you with our history more quickly than a visit to the local church, and so I took myself off to the town’s glorious gothic abbey. Because it has less stained glass than many church buildings of similar significance, the sunlight brought out the warmth of the Bath limestone, especially the stunning fan-vaulting of the roof.

The great east window was blown in by a German bomb in 1942, during the now largely forgotten “Baedeker Blitz”, when the Nazis attempted, in the words of a spokesman for the German Foreign Office, to “bomb every building in Britain marked with three stars” in the famous guide. The effect of high explosive on the human body is indiscriminately terrible. But there is also something particularly distasteful about attempting to obliterate a people’s history: it reeks of the Taliban.

Goebbels said the English belonged to “a class of human beings with whom you can only talk after you have first knocked out their teeth”.

He chose the wrong part of the body, for the churches, abbeys and cathedrals of England are its heart. The Anglican church may now be in a terrible state, but the memorials tell tales of centuries of belief. One panel sang the praises of a man whose virtues included being “indulgent to inferiors”, and I should have liked to be present when a family unveiled a memorial conveying their expectation of their father’s “blessed immorality”: the careless stonemason had likely escaped to the pub by then.

When I mentioned the inscriptions later to a friend, it turned out I had missed the best of the lot, to a pious woman of whom it was said that “she lived with her husband 50 years and died in the confident hope of a better life”.

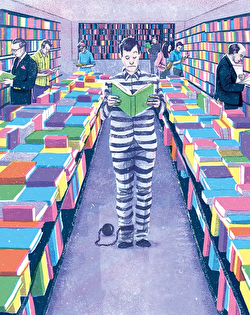

During a talk in London, a man in the audience stood up and said he had been following my career with interest. I replied that I had been following his with interest, too, and thought he had turned his time in Pentonville to good account. Afterwards he came up and asked how on earth I had known he’d been in Pentonville. I hadn’t, but it turned out he had spent served several months there for contempt of court, after cheeking some old bully of a judge.

What are the chances of that happening?

There was also a trip to Jersey — one of the more recent victims of the plague of literary festivals that have spread across the country. I thought the only things they read in Jersey were bank statements and the fine print of tax regulations. I was wrong.

After a rather jolly event, I had the chance to explore the island, famously occupied by the Nazis in the second world war. The great underground hospital built by slave labour was closed to visitors the day I was there. But there are German gun emplacements and subterranean ammunition stores all along the miles of coastline. Some have been turned to productive use, as mushroom and turbot farms, for example. Others are being tarted up with salvaged artillery pieces to act as leisure attractions. Being old enough to remember conversations with veterans of the war, I’m uncertain about the point at which evidence of brutality becomes merely diverting. I suppose 70 years since the end of the war is a decent enough interval, though I’m not really sure.

Standards of service in England have improved hugely with the advent of young continental Europeans taking advantage of the English they have been taught at school: it is the Malay of the modern world — widely understood and easy to speak badly. Quite why the aviation industry has chosen to encourage native speakers of English to act as if it is their second language is anyone’s guess. But there can be no other explanation for the gibberish issuing from so many airport public address systems. Just before a flight to another signing — in Dublin — some clown warned sternly that she was making “the last and very final call” for boarding.

I grow old, I grow old. Moaning about grammar is the business of the broken-down and irrelevant. So I have decided on my first New Year resolution. I shall try to give up grammatical pedantry.

Like other parents, I groaned when I saw that even teachers’ comments on my children’s essays were misspelled. It matters only, apparently, that you can make yourself understood. But once words are thrown about in a devil-may-care fashion, they lose all force. Of course, everyone is free to ignore the rules of grammar. But then the same is true of personal hygiene.

Still, I am resolved never again to interrupt a cabinet minister in the middle of a sentence because they say “less” when they mean “fewer”. The years of tutting at greengrocers’ apostrophes and spluttering at misuse of words like “literally” are over. The game is abandoned. Yet calling in to see the great medieval Book of Kells in Trinity College, Dublin, I discover that the very first explanatory panel in the exhibition claiming that “over 1,000 years ago Ireland had a population of less than half a million”. I know the wonder of the manuscript is its illustration. But when even Ireland’s greatest seat of learning confuse “less” and “fewer”, we pedants must give up and go home.

Article courtesy of The Financial Times. Original article here.