There is a photo on the wall.

It was taken, most probably, in the spring of 1915 and shows eight uniformed men in the jaunty confidence of youth, bed rolls slung over their shoulders.

They stand, arms around each other's shoulders, caps askew, one with a cigarette in his mouth, another with a pipe.

They smile cheerily. The bright spring sunshine leaves deep shadows on their foreheads.

In the middle, arms folded, a young man with a heavy moustache leans on a road sign declaring: 'DANGEROUS! KEEP OFF THE TAR'.

This is my great-uncle Charlie.

He has a Red Cross badge on each shoulder and grins broadly. In his entire military career Uncle Charlie won no medals for bravery, never advanced beyond the most junior rank and almost certainly neither killed nor wounded a single German.

He had enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps and his job was to save lives, not to take them.

The 1911 census records Charles Edmund Dickson as a 20-year-old living in Shipley, working as a 'weaving overlooker' in one of West Yorkshire's numerous textile factories.

Uncle Charlie looks a slightly unconvincing soldier. He fills the uniform, for sure. In fact, he looks as if, with a bit of time, he could more than fill it.

On August 7, 1915, this bright young Yorkshireman, with his affable, cheery face, was killed in Turkey.

Uncle Charlie's is one of 21,000 names carved around the Helles Memorial, a great stone obelisk at the tip of the Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey, surrounded by fields of nodding grain and clearly visible to the boats that run up and down the coast.

He was my mother's father's younger brother, dead well before she was born. Yet as children we were all familiar with him 70 or more years later -- Uncle Charlie was a present absence.

I often meant to ask my mother what she knew of how he had died, but I never did, and now she's dead I never will. How exactly he died may never be known, but the causes and circumstances of his death are easier to explain.

His detachment had been despatched to Gallipoli as part of First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill's ill-conceived attack on the 'soft underbelly' of the enemy, its purpose being to relieve the stagnation of trench warfare in France and offer a decisive breakthrough.

The scheme was one of the most wrong-headed, incompetently managed and murderous of the entire catastrophe. The idea had been for the Royal Navy to blast its way through the Dardanelles, the narrow strait that leads to Constantinople (as Istanbul was then called) and, by attacking Germany's ally, Turkey, to open a new front.

When the Navy discovered that Turkish mines and artillery made it impossible, British generals compounded the disaster by putting tens of thousands of men ashore in an attempt to destroy the Turkish batteries and safeguard the sea passage. British and Allied soldiers had to fight their way out of the sea and then scale cliffs and hillsides in the face of well-established Turkish machine-gun positions.

After the best part of a year of misery British commanders admitted defeat. Clement Attlee, later to be Labour's 1945 Prime Minister, was one of the officers in charge of the evacuation of the peninsula: the retreat was the only successful part of the entire operation. The family never learned precisely what killed Uncle Charlie.

Was he machine-gunned to death? Was he one of the thousands who had been weakened by the dysentery and typhoid that quickly spread among the men, pinned down in disgusting conditions in the gullies below the enemy machine guns for days on end?

The memory of some others who died there has been kept more conscientiously alive.The deaths of more than 11,000 Australian and New Zealand soldiers at Gallipoli are venerated as sacred parts of their nations' histories.

All I know about Uncle Charlie is contained in an old, brown, brokensided cigar box found among my mother's effects when she died in 2009. Inside, at the top of the small bundle of documents and effects, was the paper every family dreaded to receive: Army Form B 104-82.

Uncle Charlie must have made it clear when he signed up that his mother, Florina, was a widow, for the printed 'Sir' with which the form begins has been scored out and replaced with a handwritten 'Madam'.

The impersonal tone resumes: 'It is my painful duty to inform you that a report has this day been received from the War Office, notifying the death of --', and here the colonel in charge of Medical Corps administration at Aldershot has inserted Charlie's name, rank and number, adding 'Number 34 Field Ambulance, of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force' in the space left blank for his unit.

'The cause of death was --', and here an entire line of the form is left empty, which the colonel has made no attempt to fill, just writing the single, unilluminating word 'wounds'. Lying underneath it in the cigar box is another form, apparently signed by the War Secretary, Lord Kitchener.

Inside a cardboard tube is yet another mass-produced letter of condolence bearing the printed signature of the king. A thick card envelope contains a 'Dead Man's Penny', a heavy bronze plaque about the size of a tea-saucer, decorated with a robed Britannia with a growling lion at her feet.

It is inscribed with Uncle Charlie's name and the words 'HE DIED FOR FREE DOM AND HONOUR.' There is more in the box. Two days before Christmas 1920, Florina received another printed form, this time accompanying a medal -- the 1914--15 Star -- 'which would have been conferred upon Private C. Dickson had he lived'.

And in September 1921 -- almost three years after the signing of the Armistice -- another official letter arrived, this time informing Uncle Charlie's mother that her dead son had been awarded the British War and Victory Medals.

There were, apparently, some 6.5 million of these issued and, together with the earlier star, they were known as 'Pip, Squeak and Wilfred', after cartoon characters in the Daily Mirror. But the letter was treasured enough to be folded and tucked intothe cigar box. And that was almost all I knew about Uncle Charlie. Family legend had it that he had faked his age when he signed up and that he was cut down by machine-gun fire as he waded ashore on his 18th birthday.

The briefest glance at the papers in the box would have shown us that was plainly untrue -- that his 24th birthday had occurred almost six months before he was killed. But this imagined version of his death seems somehow to express a greater truth than the mere facts.

How many other families in Britain have some similar ancestral story? In the 99 years since it began, the First World War has slipped from fact to family recollection to the dusty shelves of history.

It is no longer our fathers' or even our grandfathers' war but something that happened to someone who might or might not have had our name, but who has nothing really to do with us.

The whole thing is now as far distant from us as the battle of Waterloo was from Uncle Charlie when he died at Gallipoli in 1915. If not forgotten, it at least nestles comfortably among a shared set of hazy assumptions: countless men mown down in the mud, all victims of numbskulls in epaulettes, all slain for no purpose.

The First World War has settled into our solid, unexamined prejudices, its causes and consequences submerged in sentiment and our belief that it was the product of (as well as an end to) our long-lost innocence, an express journey from naive enthusiasm to bitter disillusion.

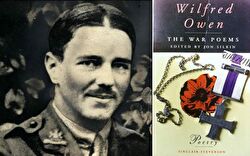

In the generations since, we have all come to see the war through the eyes of Wilfred Owen in 1917: 'What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?/ Only the monstrous anger of the guns.' When Owen used the phrase 'Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori' ('It is sweet and right to die for one's fatherland') as the title for another poem, he could assume his readers would get the bitter reference to Horace, whose original was meant in earnest.

Google the Latin phrase now and the first 600 listings are all drawn from Owen's poem. It is fine verse but was there really nothing more to the conflict that convulsed a continent than the 'old Lie'? The First World War was as consequential as the fall of Rome or the French Revolution.

The immediate political repercussions were obvious: if so many young men had not lost their lives, it is likely that a militaristic Germany would have built a European superpower. The thwarting of German ambition created the conditions for the rise of fascism, and set off the Russian revolution that brought in seven decades of totalitarian rule and the Cold War.

The war finished the Ottoman empire and consigned the great aristocratic dynasties of the time, the Romanovs, the Habsburgs and the Hohenzollerns, to history. And the war was the mechanism by which Britain became recognisably its modern self.

Victorian time travellers transported from 1880 to the spring of 1914 would have found themselves pretty much at home. If they had travelled on a further four years, they would have been baffled by what they saw.

There were more than 700,000 British participants who never lived to see the new society, so if the eight friends in Uncle Charlie's picture suffered at the same rate as the rest of the Army, by 1918 four of them were dead, wounded or missing.

The only way we can grasp the sheer scale of this loss is to simplify it, resulting in the received version of these vast and complicated events -- the common man ordered to advance into machinegun fire by upper-class twits sitting in comfortable headquarters miles away -- a version that has sustained us for generations. It is such an easy caricature.

By 1936, David Lloyd George, who had been Prime Minister during the war, was talking of how 'the distance between the [generals'] chateaux and the dug-outs was as great as that from the fixed stars to the caverns of the earth', as if they preferred to be miles away from the action, when the truth was that in an age before radios, with communication by runner, messenger dog or carrier pigeon, the closer a commander was to the action, the fewer men he could control.

The attitudes of many of today's grandparents were shaped by the 1960s musical Oh! What A Lovely War with the British commander, General Haig, manning a turnstile to charge visitors to watch the carnage, while staff officers played a game of leapfrog. The same point of view underpinned the 1989 comedy series Blackadder Goes Forth.

When General Melchett tells Captain Blackadder that he will be 'right behind him' in the charge over the top, Blackadder mutters, 'Yes, about 35 miles behind.' Blackadder was comedy -- and rather a good one -- yet it is now played to school classes by history teachers. It seems to have become much easier to laugh at -- or cry about -- the First World War than to understand it.

There is something unsatisfactory about all this received wisdom. Can British generals really have been as indifferent to the fate of their men as the image of 'lions led by donkeys' suggests? Is this adequate as a reading of the entire war?

Of course they blundered. But in the end the donkeys and the lions won. As for the poisonous legacy and the unrealised promises of peace, these surely were not the fault of the generals.

Yet we are stuck with the default conviction that the First World War was an exercise in purposelessness. That was not the prevailing view at the time. On the contrary, Lord Kitchener's appeal for volunteers in the early days of the war had been so successful that lines at recruitment offices snaked for blocks down city streets.

The great harvest of anti-war memoirs and novels did not appear until ten years after the Armistice. Throughout it all, the resolve of the British people did not weaken.

Why did men continue to fight if the thing was so obviously families continued to support them and to suffer the separation, the anxiety, the rationing and the rest of the privations of wartime. They endured to victory. To understand how this was possible we need to get beyond the trite observation that the deaths of Uncle Charlie and his comrades were no more than a tragic waste.

What aggravates our ignorance is the false assumption that we do understand the First World War. We need to cast ourselves back into the minds of these men and their families, to try to inhabit the assumptions of their society rather than to replace them with our own.

How, one wonders, would the teacher explain to her students that after writing his celebrated denunciations of battle, Wilfred Owen returned to the Western Front to continue fighting and, furthermore, described himself in his last letter to his mother as 'serene'? It was, he said, 'a great life'.

The retrospective narrative of innocent conscripts, dullard generals and boneheaded battle plans has become tiresomely familiar. It is precisely because the Great War changed so much that we understand it so little. Before it began, the country had enjoyed half a century of being told that theirs was the greatest nation on earth.

We have since had generation after generation of international decline. The middle and upper classes of 1914 had been brought up on ideas of privilege and obligation, which made them respond to what they were convinced was the call of duty.

Ordinary people were accustomed to being bossed about. Even the idea of 'sacrifice', entirely acceptable at the time, has been lost to us, discarded along with religious belief and replaced with a cost-benefit analysis which deems such sacrifice 'pointless'.

As to why men volunteered to take part in such carnage, the short answer is they did not: the war they went off to fight in 1914 was nothing like the war of even one year later. As for the 'donkeys' in command, they were no better informed than anyone else, even if ignorance is no excuse.

Today, we lack the means to imagine what they thought they were doing. The war is the great punctuation point in modern British history, the moment when the British decided that what lay ahead would never be as grand as their past; the point at which they began to walk backwards into the future. There is a sense in which, like the desperate parents who could not believe their son was dead, the entire nation has been conducting a form of séance ever since.

Courtesy of The Daily Mail. Original article here.