Wilfred Owen was born on March 18, 1893, in Shropshire, and died on November 4, 1918, aged only 25. He left behind a legacy of superb poetry. In this article, TV presenter and historian Jeremy Paxman looked back on the extraordinary achievement of Owen, who abominated war yet died a great warrior. This article was first published in The Telegraph in November 2007 to coincide with the BBC programme Wilfred Owen: A Remembrance Tale. Mr Paxman's fee for the article was donated at his request to the Poppy Appeal.

For me, he is the greatest of all the war poets. But there is nothing original in my enthusiasm. I don't suppose there's a thoughtful student in the land who is unaware of Wilfred Owen's best-know poem, Dulce et Decorum Est. Indeed, it tells us something about our pervading cynicism that Horace's words are now taken more readily as sarcasm than at face value.

It is often assumed – as a student, I made the mistake myself – that the poem's author was some sort of bitter, jaundiced pacifist. But the enigma of Wilfred Owen is that he was anything but that.

The fascination of his life is his embodiment of contradictions. It is true that he was not among the first to answer the call to bash the Boche. Indeed, he seems to have been a rather fey and precious young man, first as a vicar's assistant in Berkshire, and then as an English teacher in France.

When he finally decided to join the Army (through the Artists' Rifles, to fit with his own idea of himself as a poet, despite the fact that he was unpublished, and, frankly, not very good, either) he was repulsed by the coarseness of the men among whom he found himself. But his letters to his mother – our main source of information about his life – show how much he changed. Initial distaste at the vulgarity of the sweaty, noisy men among whom he was obliged to live became a genuine love.

By the end of the First World War, he had become not only their advocate but a true military hero himself. The vital event was the horrific experience of having to take shelter from German artillery fire on the side of a railway embankment. Owen was trapped there for days, lying amid the remains of a popular fellow officer. It triggered shell-shock. Early victims of the condition had had to put up with the boneheaded prejudice of generals who considered it be merely the mental equivalent of Malingerer's Back.

The inscription on the headstone of war poet Wilfred Owen, at the war graves cemetery in Ors, France

Some of the early casualties had even been "treated" with electric shocks, on the theory that, if the pain was bad enough, they might decide that the terror of the trenches was preferable. Owen was luckier, and, at Craiglockhart War Hospital, near Edinburgh, came under the care of a regime that believed in a form of occupational therapy. By chance, a fellow officer and poet, Siegfried Sassoon, was also a patient there, having been sent to Craiglockhart for having the temerity to publish a letter criticising the conduct of the war.

The manuscripts of the surviving Owen poems, kept in a vault at the British Library, show Sassoon's handwriting on Owen's poems, evidence of the vital role the relationship would have in the refining of his poetry. The most remarkable aspect of Owen's stay at the hospital, though, is the fact that he emerged not merely as the author of some of the most stunning poetry of the 20th century – and the voice of a generation – but that he was also determined to return to the front line.

Sassoon begged him not to go, and even threatened, at one point, to stab him in the leg to prevent him doing so.

But Owen would not be deterred, and the man who returned to France was a superb soldier. In one attack, in which he captured a German machine post and scores of prisoners almost single-handed, he writes to his mother with the extraordinary expression that he "fought like an angel". The events earned him a Military Cross. The last letter home, written at the end of October 1918, describes how he is sheltering with his men in the cellar of a forester's cottage in northern France, before an attempt to cross the canal that marked the front line.

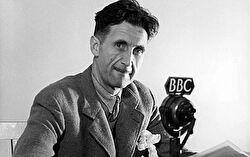

Wilfred Owen photographed in uniform in 1916

Crammed into the smoky fug – he says he can hardly see by the light of a candle only 12 inches away – the men are laughing, sleeping, smoking or peeling potatoes. "It is a great life," he writes joyfully, and goes on, "you could not be visited by a band of friends half so fine as surround me here." Utterly wrong, then, to think of him as some sanctimonious hand-wringer. The paradox of Owen – that he had become a first-rate warrior while abominating war – is what gives his poems their unique strength.

While filming Wilfred Owen: A Remembrance Tale for the BBC, we talked to Justin Featherstone, a young major who won the Military Cross in Iraq. I had imagined that he would prefer Rupert Brooke's vision of "The Soldier": If I should die, think only this of me That there is some corner of a foreign field That is forever England. Not a bit of it, he said. Owen is the soldier's poet, because he understands what soldiering is really like, the horror and fear, alongside the dry-throated heroism.

Brooke's sonnet may be the one for military funerals. Owen is the poet for the living. And yet Owen did not live to see peace himself.

After sheltering in the cellar, he and his men were deployed to the banks of the canal, at Ors. In the early morning of November 4, 1918, they were given the order to storm the canal, in the face of withering German machine-gun fire. Owen never reached the other side. Seven days later, as his mother stood listening to the church bells peeling for the end of the war, she received the dreadful telegram with the news that her precious son was dead. Is it because he never lived to versify about the mundane pleasures of peace that Owen is the greatest war poet? It's part of it, of course: his own life is a perfect example of the loss of illusions and innocence that the war brought to our entire civilisation.

Most of all, though, Owen's poetry, like his life, scorns easy attitudinising. Of course, "Dulce et Decorum Est" was written to rebut the jingoistic bilge of "poets" such as Jessie Pope who produced doggerel in the Daily Mail ("A gun, a gun to shoot the Hun," etc.) But it is Owen's intense respect for the soldier that makes his poetry so powerful. Those who did not return have their meticulously maintained stone memorials on the fields of Flanders. But their memorial in our minds is largely built by Wilfred Owen.

Dulce et Decorum Est by Wilfred Owen

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep.

Many had lost their boots But limped on, blood-shod.

All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime…

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt,

the blood Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud Of vile,

incurable sores on innocent tongues,

– My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Courtesy of The Daily Telegraph. Original article here.