I am just outside the town of Cochrane in southern Chile. It’s not much of a place — a few thousand people and some dull buildings plonked in Patagonia in the 1950s and only connected by land to the rest of Chile since the construction of a dirt road 25 or so years ago. And yet what a person it commemorates. Even as an enthusiast for imperial history, I confess I was unfamiliar with him: a consequence of my inability to appreciate the Jack Aubrey novels of Patrick O’Brian, I suppose. Admiral Thomas Cochrane was O’Brian’s model but, as so often, real-life derring-do far outstrips the fictional version.

Like many empire-builders, Cochrane was a Scot, who joined the Royal Navy as a midshipman in 1793 and made a fortune from the prize-money that came from brass-necked adventurism. Even in his first command, a small sloop, he captured more than 50 French ships, most of them of greater fire — and manpower.

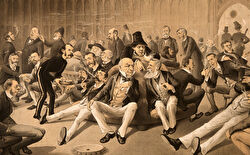

When he was sacked from the navy for being involved in a stock exchange fraud built on rumours that Napoleon was dead, Cochrane took himself off to South America and fought for Chile in its war for independence from Spain. Again, his exploits became the stuff of legend. And he went on to fight for Greek freedom from the Ottomans, before being granted a royal pardon and reappointed to the Royal Navy. It’s a huge stretch of imagination to believe he belonged to the same organisation as a hapless bunch of clowns who surrendered to the Iranian Revolutionary Guards eight years ago this month.

Cochrane’s name lives on in the Almirante Cochrane, a frigate in the Chilean navy, previously the Royal Navy’s HMS Norfolk. Before that, the name was borne by another Chilean vessel, the Falklands war veteran HMS Antrim. The Chilean navy subsequently got 16 years’ service out of the ship, which rather makes you wonder about why the Ministry of Defence sold the thing.

A military friend tells me that before the first world war the German expat community in Patagonia offered to raise an army of 100,000 and to capture the Falklands for the kaiser. In the event, the islands were the scene of a decisive British naval victory over the Germans.

When I pointed out to a Chilean friend yesterday that one of the consequences of the 1982 conflict was that current British policy in the South Atlantic is now more or less dictated by a gaggle of sheep farmers, I was told, “But if the Argentines took over, that place would be overrun with stray dogs in no time.” It’s a new definition of civilisation but not a bad one, I suppose.

Still in Chile, I’m on a fishing trip with, among others, my old friend Mark Clarfelt, who owns some rather choice fishing on the river Test and is about to form a Jewish Fishing Society. Why, I wonder, is it that Jews seem to be so little associated in Britain with country sports? Perhaps it is to do with the fact that these activities are more usually associated with tweedy types, when one of the traditional Jewish stereotypes is more often metropolitan, someone more at home in Le Caprice than at a riverside barbecue.

I have, however, an awful feeling that some of those tweedy types may have been part of that nasty undercurrent of anti-semitism which so stained the British upper classes between the wars. But just how many of them realised that the apostle of dry-fly fishing for trout, FM Halford, was the son of German Jewish immigrants, and originally known as Frederick Michael Hyam?

En route from Chile I had to change planes in Charles de Gaulle airport and made the mistake of thinking there was certain to be somewhere decent to eat in the self-styled world capital of gastronomy. There wasn’t.

After a wait of 15 minutes I managed to extract some dried-up rice from a self-service food bar. It was worse than most in-flight meals served when you’re seated by the lavatories at the back of the aircraft.

We all know France is in a terrible state but who had any idea it was this bad? If the shade of the great French chef and restaurateur Georges Auguste Escoffier heard about it, you’d be able to boil a couscoussier on the top of his head.

I am now in Tunisia, which abounds with reminders of the folly of imperial grandeur — from much earlier periods than Cochrane’s glory days, of course. It has, for example, a Roman amphitheatre at El Jem that is better preserved than Rome’s Colosseum.

Visiting almost any historical site is a wonderful antidote to having to listen to political posturing: I bet the leaders of the Phoenician empire made Vladimir Putin sound like an ice-cream salesman, and yet how many of us really know anything much about it and its great city at Carthage? Cato the Elder’s bitterly malevolent “Carthago delenda est” (“Carthage must be destroyed”) is surely worthy of Hitler or Stalin.

Cato may have got his own way. But the Romans, who then built their own city in Carthage, were invaded in their turn, and the place — along with many of the country’s other stunning ancient sites — has been repeatedly plundered for building materials over the centuries since. But the local museums still have some astonishing pieces including one of the best collections of mosaics in the world and some remarkable sculpture.

Outside the museum at Carthage are some beautiful life-size human statues, each sadly decapitated. Did that happen with the invasion of the Vandals, I asked? No, I was told, much of it was the consequence of the Muslim invasion, because of their religious hostility to representations of the human form. “When the Vandals invaded, they just broke off the statues’ noses,” said my guide. As one of those blessed or cursed with a weighty proboscis, I’ve always liked the fact that the Romans admired a good conk. That sort of vandalism is just what you’d expect of, well, a Vandal.

Courtesy of the Financial Times. Original article here.