It is the coldest night of the year so far, the wind blowing snow flurries over the staggering party-goers shouting and laughing their way through Soho in central London. Among them walk two police officers in navy trousers and high-vis jackets. The drug-dealers whistle to each other that the law is about.

A taxi is at the kerb, its doors open to clear the smell from the vomit on the floor. The passenger has stumbled from the vehicle without paying and is now lying on the ground, saying she has neither money nor card and, anyway, can’t remember her pin number. It is only 9.30pm.

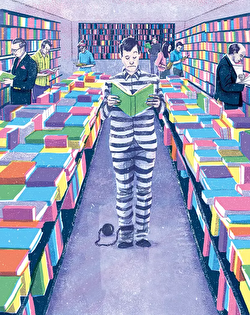

As the night goes on, there will be countless more scenes worthy of some modern Hogarth, generally involving alcohol or drugs.

“Spice”, a dangerously unpredictable synthetic cannabinoid, is the drug of choice for many of the unfortunates on the street. But the spice of Soho streets on a Friday night is the stench from someone’s heaving stomach.

Officers Steve Muldoon and Rachel Coates have seen it all a hundred times before. Muldoon, 33, commutes to work from Northamptonshire — like many in the public sector, he cannot afford to live in the city he helps keep safe. Coates, 27, his patrol partner, has both undergraduate and postgraduate degrees and lives in east London. “I enjoy it for the contact it gives me with people,” she says.

For all the world is here: tourists, prostitutes, foodies, pickpockets. Coates and Muldoon know the locations of the bars and dosshouses and how Soho’s many brothels skirt the law. They greet regular customers by their first names, say hello to the bouncers and know which part of Soho is favoured for Class A drugs and which for Class B.

After midnight, they will join colleagues to erect a “knife arch” (something like an airport body scanner), hoping to catch gangs of locally known Somali muggers bent on robbing those unwise enough to have a phone, watch or piece of jewellery on their person.

But now, at 10.30pm, they recognise a man lying under a shop awning who has skipped a court order. The handcuffing is punctuated by his screams: he is an alcoholic and claims the cuffs have cut the circulation to his hands.

Muldoon has a small photograph of his children hanging from the ring holding the handcuff key. It helps him when someone is shouting, swearing or, as happened once, biting his face.

Around 11pm, having chatted to others who are clearly, and sometimes alarmingly, mentally ill, we move on to rough sleepers said to be causing a nuisance. The officers speak to an ageing Irish woman who has somehow taken the plastic boot off her broken foot after bedding down on the pavement beneath a theatre poster for No Man’s Land. “Tina,” says Muldoon, “what would you like me to do? Do you want to go to hospital?” As long ago as the 1970s, a previous Metropolitan Police commissioner, Sir Robert Mark, lamented that the service had become “the anvil on which society beats out the problems and abrasions of social inequality, racial prejudice, weak laws and ineffective legislation”.

Mark was a thoughtful policeman, in a different league to most of his successors. But he was agonising over the purpose of policing before the rise of “preloading” (drinking before going out), crack, the closure of long-stay mental institutions, “legal highs”, 24-hour pub opening, the failures of so-called Care in the Community and long before The Cuts, which have finally hit the police.

Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe, the retiring commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, the biggest police service in the country, has muttered repeatedly about a looming need to “ration’” policing in the capital. “The bottom line is there will be less cops,” he told LBC radio, tasering English grammar to make his point.

In the early hours, there will be singing and brawling and men and women urinating — and worse — in the street. The night among the flotsam and jetsam of humanity will continue in similar fashion until the police shift ends at 6am. For protection the officers carry a canister of CS gas, an evil-looking extendable baton, and a pair of handcuffs. No tasers: they consider themselves fortunate that, in central London, back-up can be with them inside a minute or so. Police officers patrolling county towns on a weekend night are much more exposed.

Let’s be honest.

How many of us would want a job that exposed us to random violence, expected us to wipe the vomit from a teenager’s face, to retrieve personal effects from a suicide’s pocket or to break the news of a loved one’s death to his or her family?

The rest of us may cross the street to avoid druggies, drunks, sweary yobs, the vulnerable and the uncared-for. The police have no such choice.

Steve White, chair of the Police Federation (representing officers from constable to inspector), drily observes that “most of the time you’re dealing with people who don’t like you”.

***

There are two things to be said about life on the police frontline. First, apart from the determination to contain a plague of muggings in London, much of an officer’s job seems to be a form of social work. Second, it is nothing to do with the burgeoning new fields of criminal activity.

In the days of Sir Robert Peel, who as home secretary established the Metropolitan Police in 1829, most crime was local and public. Much of it is now conducted in private and is not necessarily local at all — the internet has enabled entirely new forms of criminality to flourish: online fraud, remote child sex abuse and great numbers of anti-business scams.

The Office for National Statistics reports that there were 6.2 million “incidents of crime” in England and Wales last year. Sara Thornton, head of the National Police Chiefs’ Council, is worried about an additional 5.6 million fraud and computer offences, which are assuredly not amenable to traditional forms of law enforcement.

Undercover officers following cyber crime online could be effective at combating the new forms of crime, but this would come at a risk. “Police visibility helps us to build trust,” she says. “The bobby on the beat still has an important place in targeted local policing. But we’ve got to be as active and visible online.”

Early chief constables followed the maxim that “the primary object of an efficient police force is the prevention of crime”. If this was ever a worthwhile yardstick, the police have failed.

According to one history of the service, in 1939 the total number of crimes committed was 300,000. By 1978 it was 2.6 million. It is now 11.8 million, when cyber crimes are included.

Peel’s country house in Staffordshire has been turned into a theme park. One of the attractions must be the sound of a man spinning in his grave.

But an escalation in crime need not be the fault of the police: the people responsible for perpetrating crime are criminals. How, then, are we to measure police effectiveness? The matters that stick in the public mind are all failures. The 96 deaths at Hillsborough stadium in 1989, the incompetence and dishonesty that left the killers of Stephen Lawrence free, the bungling and vindictiveness that humiliated Cliff Richard and Field Marshal Lord Bramall may make headlines, but there’s plenty more — failure to protect victims of child sex abuse or an officer falsely claiming to have witnessed a cabinet minister labelling a colleague a “pleb”.

A general impression of the police may come from the newspapers but the public’s experience is more likely to be shaped by their dealings with an individual officer. Hard to measure though it is, there does appear to have been a shift in attitudes. “I didn’t even report it — no point,” is the commonplace observation about small-scale criminality — people know they may well only get a letter blathering about whether they would like comfort from Victim Support.

Even police officers talk of “the persecution of motorists” for traffic offences, bringing swaths of the middle class who think they have done no serious wrong into contact with the police. But mostly, the complaint is of invisibility. Nick Herbert, a Conservative MP and former police minister, represents a largely rural constituency in West Sussex.

“Many of my constituents claim that they never see a policeman,” he says. In that part of the world, they’re probably telling the truth.

Since the police are absent from so many lives, perhaps we could do without them? It is a function of democracy that laws are agreed upon by the citizens. Application is everyone’s responsibility. Article Seven of Sir Robert Peel’s Principles of Law Enforcement (1829) states: “The police are the public and the public are the police.”

Yet every day the police make their own choices about which laws to bother enforcing. Their unique privilege is to be the only ones among us entitled by law to decide when it may be appropriate to use force. This means they are emphatically not the public. And, increasingly, the police look and seem different from the rest of us.

To be mentally ready to face a youth with a knife or the aftermath of a fatal accident, they must make themselves increasingly remote: wariness easily becomes a way of life.

Their training accentuates how different they are from civilians, and long periods spent together consolidate attitudes dividing the world into “them” and “us”. Ever since the deployment of personal radios, police officers have acted not as individuals but as part of a force.

***

Peel’s aphorism about the public and the police is still much quoted, but something has gone awry.

The force Peel assembled in 1829 was a consequence of the changing patterns of population, as the industrial revolution drew people into ever greater conurbations.

Peel chose to dress them in dark blue rather than military red, with high hats and swallowtail coats (with their truncheons concealed inside) to accentuate the idea that they were members of the public.

He favoured big men for the job (a minimum height of 5ft 10in survived into the late 20th century) and set their wages on a par with those of an agricultural labourer. Members were on call seven days a week and constables carried a chequered band to wrap around their arms when duty suddenly called. The band was still visible on the uniform of the avuncular George Dixon in the BBC television series Dixon of Dock Green (1955-1976), which for many people marked the apotheosis of the British police: unlike gun-toting foreign forces, the series showed the police using local knowledge and common sense to solve or prevent low-level crime. The series survived 20 years, finally displaced by Z-Cars, which presented policing as a matter of fast cars, flashing lights and sirens.

But for all that, the British police are distinctive and civilised. Most officers perform their duties without firearms and Peel rejected the idea of a national force as nastily reminiscent of a standing army. (France has not one but three national forces, reporting to ministers, and the very word police is French. Not that it makes them any more liked by French people.) So England and Wales plod into the future with 43 separate forces, each with its own chief constable (of variable quality though, increasingly, of similar colourlessness), and far too often competing, rather than collaborating, with each other.

Everyone agrees it’s too many but no one can settle on what would be a better number. Half a dozen? One? Four years ago, Scotland merged its eight police forces into Police Scotland, a single force covering 30,000 square miles. While it is said to have led to better policing of organised crime and terrorism, it was widely seen as a political project and is not considered much of an advertisement for consolidation.

There may be no logical reason for resisting a national police force. It’s just not the way we do things here.

But we do need to reinvent Peel’s view of the police as the public for our modern age, a time when the police have become remote and where all authority is questioned. It is this, more than anything else, that lies behind the drive to recruit more officers from ethnic minority communities, so the police can at least look like the cities they serve.

(Between April and December last year, 27 per cent of Metropolitan Police recruits were from black and ethnic minority backgrounds — inadequate, but much better than it was.) It has always been the case that the men and women who protected the property of the middle class were themselves working class. Peel stipulated that only men “who had not the rank, habits or station of gentlemen” should be enrolled. That may not last much longer.

The obvious solution to an explosion in cyber crime is for the police to be better educated. Yet “professionalising the police” has, in effect, meant keeping senior posts for lifers: every head of the Met since Robert Mark has, like him, begun his career as a constable. About a third of entrants to the Met are now graduates (about a third are also female: no current chief constable could expect to get away with the remark attributed to a boneheaded senior police officer in the 1980s that “a lady policeman is a contradiction in terms”). But, in its feel, the institution remains overwhelmingly male — all six of the senior officers of the Police Federation are men.

Cressida Dick, just appointed as the new Metropolitan Police commissioner, has her work cut out. Sara Thornton, who served eight years as chief constable of Thames Valley, visibly shuddered when I asked her whether the job was lonely, before saying: “Very lonely.”

Policing needs a lot more thought. Yet proposals that the police consider direct entry and accelerated promotion to encourage more of the highly educated to apply for jobs have been greeted with outrage from the Police Federation. Four out of five Met officers are constables, with an average age of 37. One policeman’s blog caught the mood perfectly — the plan for an officer-class entry was “an insult”: you could not command the respect of fellow police unless you had at some stage broken up a pub fight.

You do not hear many similar complaints about the recruitment of army officers, and the recently established College of Policing has rightly pressed ahead with a small number of direct-entry places at inspector and superintendent level. It is a recognition that the police have become rather unsophisticated by comparison with other trades. The question is how much sophistication is required to deal with some of the malodorous tasks expected of them.

But it’s not a bad life. An experienced constable in London can earn £40,000 per year, a superintendent almost double that, and the newly appointed Met commissioner more than six times as much. There’s a state-backed pension. Unlike most of us, a well-behaved police officer cannot be made compulsorily redundant. Yet last year’s survey by the Police Federation showed more than half its members suffering from low morale. For them, the policeman’s lot is never a happy one: the federation has been vying to knock the Prison Officers’ Association from its perch as Britain’s Most Lugubrious Trade Union for years.

The most commonly cited reason for low spirits was “the way the police are treated”. Yet late last year an Ipsos Mori poll (if you take such things seriously) discovered that trust in the police had overtaken that placed in the clergy, hairdressers or television newsreaders. (Journalists and politicians continued to wrestle for the position of least trusted. Sadly, opinion pollsters were not included as a category.)

The police’s problem is less with the public than with politicians. Tony Blair famously talked about “the scars on my back” incurred while attempting to reform the public sector.

He did not include the police, to whom Labour governments persistently pandered. Perhaps it was because Labour was generally trusted on schools and hospitals that it had enough confidence to attempt reforms there. When it came to crime, though, there was only their meaningless slogan about being “tough on the causes of crime”. It was the Conservatives, for so long the “party of law and order”, that saw the need for change: the reputation endowed the party with the confidence to take on the police.

An independent report in 2011 declared officers were better paid than they had ever been. Why, then, should the police remain immune to cuts affecting every other area of the public sector? A government investigation into police pay had previously been trampled into the mud by the Police Federation. But this time the Conservatives were better prepared.

When the federation began an entirely predictable campaign warning about “Christmas for Criminals” if cuts went ahead, the herald angels weren’t listening.

Theresa May, after enduring the ire of the Police Federation, who had invited her to address them as home secretary, told the federation in 2014 that the hundreds of thousands of pounds of public money the organisation received each year — for what were effectively trade union tasks — would be cut off. More howls. But she wasn’t done. She appointed the clever and spiky former rail regulator Tom Winsor as chief inspector of constabulary, the first occupant of the post not to have worn the uniform himself.

In place of police authorities, May introduced directly elected police and crime commissioners, to whom most police forces are still expected to report. The turnout in these elections has yet to exceed 50 per cent but some of those appointed, such as the former Labour minister Vera Baird in Northumbria, are impressive individuals and unlikely to be a pushover for any chief constable.

These changes were recognition that things weren’t working properly. Some much-loved habits of the past will have to change further. When the government has decreed, for incomprehensible reasons, that 50 per cent of school leavers should go to university, there is no reason why similar diktats cannot be made about police recruitment. The whole culture could do with an opening up to alternative views — and not just in television dramas.

A trust rating of 70 per cent isn’t bad, even if it does mean that three out of 10 people don’t trust the police.

Perhaps it will never be much higher; early alternative nicknames for the bobbies — blue drones, crushers or blue locusts — speak to that different perspective. Then again, the British middle class have always romanticised their police. Though few as elegiacally as The Times’ 1908 claim that “the policeman . . . is not merely guardian of the peace; he is the best friend of a mass of people who have no other counsellor or protector.”

“The best police in the world”? Not if you judge by the scandals and riots, nor even the shrugging shoulders of much of the middle class who seem to have lost faith in the speedy resolution of crime. But preferable to some paramilitary thug answering to the minister of the interior. The evidence of a secure society is the absence of crime and disorder, not the visible demonstration of police power and the whiff of CS gas on the street.

For those with eyes to see, the early warning signs of social discontent abound — in the growing gap between rich and poor, the obscenities of the property market, the diminishing employment prospects for so many young people. If there is more unrest, it will again fall to the police to defend the interests of the powerful against the powerless. Though it is not the role they would necessarily choose for themselves.

Article courtesy of The Financial Times. Original found here.